Strengthening Plants with Diatomaceous Earth

Strengthening Plants with Diatomaceous Earth

By Grubbycup from Maximum Yield Magazine 2021

While diatoms provide plenty of oxygen to Earth’s atmosphere, their silica exoskeletons (diatomaceous earth) strengthen plants and provide protection from insect damage, adding a natural tool to any gardener’s toolbox.

Diatoms are a diverse group of single-celled algae made up of thousands (or by some estimates millions) of species whose silica cell walls are collected as skeletal remains and used as diatomaceous earth (DE).

Primarily found as part of the phytoplankton of both fresh and salt waters, diatoms account for nearly half of the organic material found in the oceans. They can also live inland under semi-aquatic conditions on wet soils, mosses, bark, or even rocks. They range in size between 200 microns (about the width of a human hair) to as small as two microns long (about the width of spider silk). In the areas they inhabit, they are invariably an important part of the food chain as a food source for filter feeders and zooplankton such as clams, snails, shrimp, and krill.

Like plants, diatoms use chlorophylls (chlorophyll A and chlorophyll C) to collect light from the sun and use that energy to convert carbon dioxide (CO2) into sugars to fuel growth using photosynthesis. This process consumes CO2 and releases oxygen. They are an important contributor to both global carbon sequestration and oxygen generation. Although tiny and often overlooked, by some estimates, diatoms are responsible for somewhere between a fifth and a quarter (or more) of the oxygen in the atmosphere.

Diatoms are distinctive for making rigid “shells” known as frustules to form their cell wall. These frustules are made from hydrated silica oxide and come in a variety of shapes dependent on the particular species of diatom. The shapes tend to be intricate and geometric, forming a protective silica cover dotted with openings for nutrient uptake and waste disposal. An organic coating helps prevent the silica from dissolving while the diatom is alive. Over 6 billion metric tons of silicon are sequestered by diatoms every year.

The cells of diatoms form in two halves, one slightly smaller than the other. During reproduction, these halves split into two separate cells. Each half of the cell grows another smaller half to replace the missing side. Over time this causes the average size of the offspring to become smaller, until a minimum size is reached. Then the smallest individual diatoms form auxospores which are larger halves to restore the size lost during the above process.

Live diatoms can be collected from the brown snot-like coating on submerged attachment points such as stones, sticks, marine plants, or other marine detritus. Diatoms can be concentrated in a sample by filling an opaque sided container with water and mud, and letting direct sunlight fall on the surface. Within a day or two, the diatoms will rise to the top in a scum and samples can be collected.

When an individual diatom dies, it will lose buoyancy, and the frustule will sink. After death the organic coating decays, and much (but not all) of the silica dissolves back into the water. In areas of dense diatom populations, enough is left to create a sediment layer formed from the vast number of these discarded frustules. While the organic components aren’t long-lived, their silica exoskeletons can remain in sediment layers for millions of years. These layers of diatom frustules can be mined, and the material collected is referred to as diatomite or diatomaceous earth.

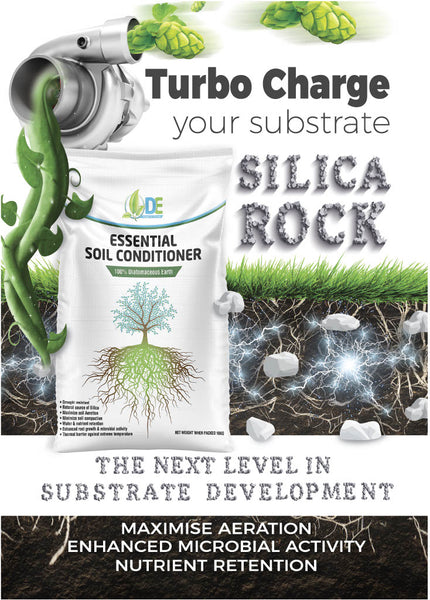

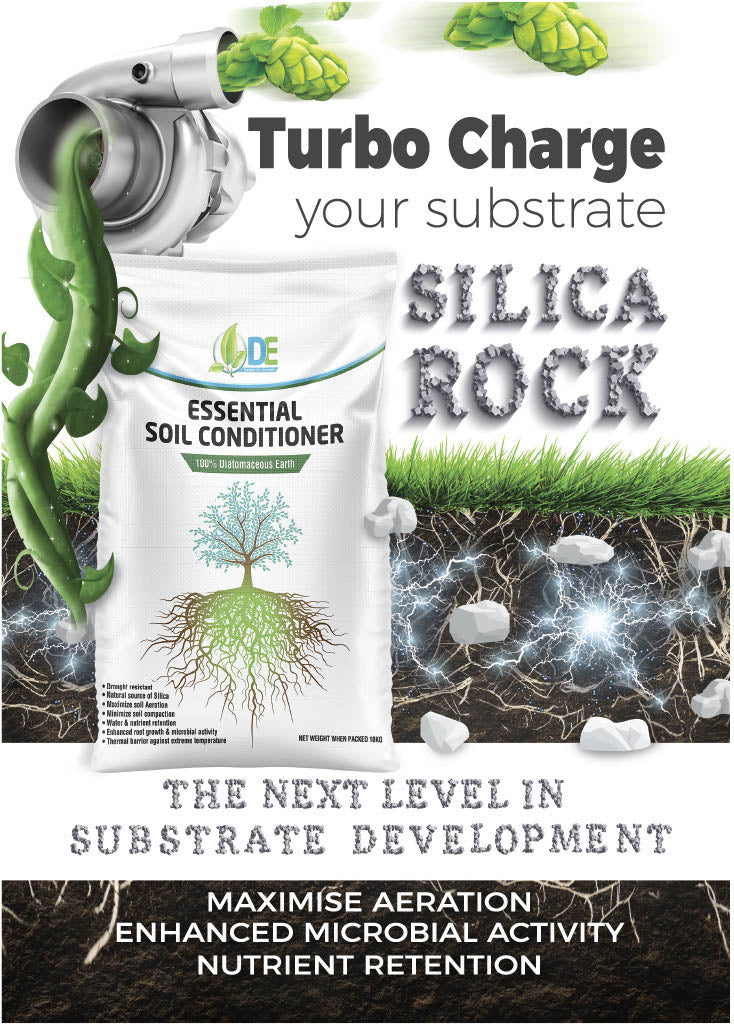

Improving Grow Mediums with Diatomaceous Earth

Depending on mining and processing, diatomaceous earth may be sold as chunks of stone or ground into a powder. Since the frustules (broken or whole) still have voids and holes, they are much lighter and more porous than a solid piece of silica would be.

Diatomaceous earth is used in a variety of ways. It is used as a mild abrasive in polishes, toothpaste, and facial scrubs. It is used as a liquid absorbent, in some flea powders, and can be used as cat litter. It is an important component of dynamite (diatomite soaked with nitroglycerin). It can be heat treated and used as a filtering material for drinking water, swimming pools, fish tanks, beer, wine, and other liquids. It is also used as an anti-caking agent in grain storage. In gardens DE is used as both as a growing medium additive and as an insecticide.

Diatomaceous earth for gardening should be amorphous silica and not heat treated or contain much in the way of crystalline silica or active contaminants. Chunks of DE may be used as a component in a growing medium. By virtue of the voids within the material, it holds both water and air well. It can be added to a potting mix or an existing soil as an improvement or used by itself as a hydroponic medium. Diatomaceous earth is high in soluble silica, and while silica is not generally considered a plant nutrient, many plants (especially monocots) can make use of it to reinforce their cell walls, which can strengthen and fortify them against insect damage.

Dry-powdered DE is used as a mechanical insecticide. It absorbs fats and oils from an insect’s exoskeleton while the sharp edges cut and damage. With the reduction of the protective fats and oils on the exterior of the insect, the fluids inside more easily evaporate, dehydrating and killing the insect.

It can be applied by either sprinkling dry or mixing with water to apply and then allowed to dry. While DE is not poisonous, breathing any dust can have detrimental health effects so precautions should be taken to avoid excess inhalation. It is frequently applied to the medium around the plant but may also be used on plants themselves. If used directly on plants, avoid harvestable portions as it can leave a (mostly harmless) residue, and avoid spraying flowers to protect bees.

Diatomaceous earth can be used in a variety of ways, and with care and judicious use can be a valuable tool to add to a gardener’s bag of tricks.